Archive for the ‘International Law’ Tag

.

.

“During the inter-bellum and throughout the war which began in 1939, innumerable articles were published in the daily press and periodicals denouncing international law, whose beautiful rules were consigned to remain only on paper as two wars, with increasing atrocity and devastation, raged throughout all corners of the world. However, if any accusations levelled at international law came from jurists, they were not only ill-founded and glib, but increasingly rare. As for opinions from non-legal quarters which decry the ineffectiveness of international law, they can be considered entirely justified, but it is not the juridical character of the law which is at fault, rather the present state of that law which has failed on account of ambitions, egos, and a lack of mutual understanding among states, which must ultimately carry the blame.”

.

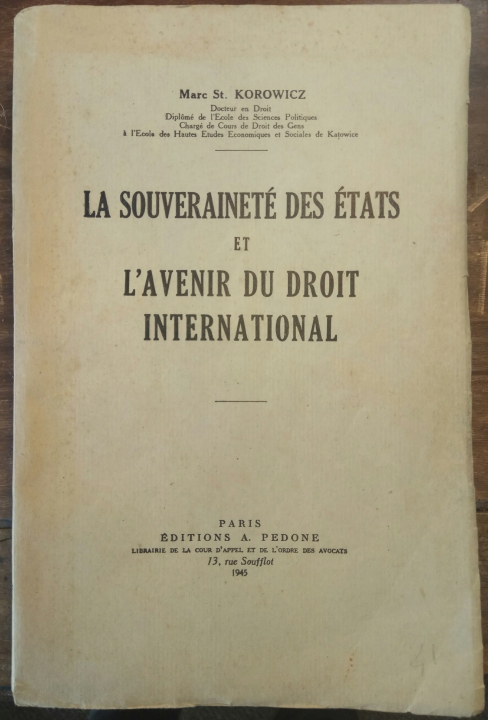

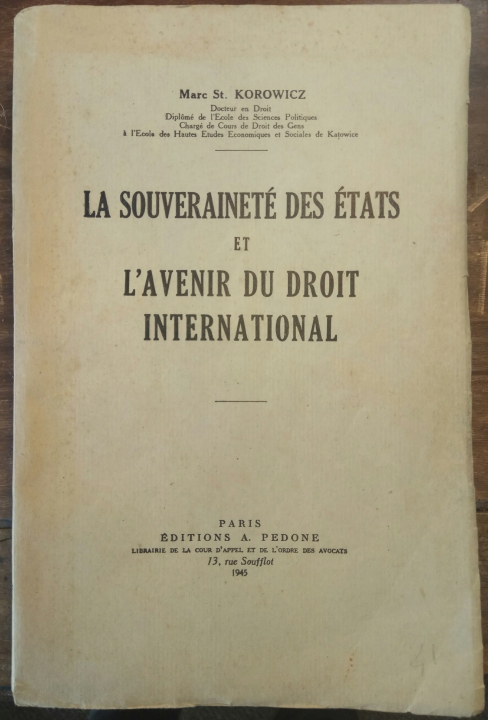

On the face of it, this shelf-parched, soft-bound tome, written in France during the Second World War, did rather well to survive this far. I recently saved it from the oblivion of a book depository in Aquitaine. The year and location of its publication, the identity of its author, the subject and content, the small number of the imprint and even the quality of the paper it is printed on are all testament to the unlikelihood of its existence let alone the likelihood it may have anything of note to say to the modern reader. La Souveraineté Des États et L’Avenir Du Droit International (“The Sovereignty of States and the Future of International Law”) was written by my granduncle Marek Stanisław Korowicz, whose story I have documented here previously. Marek, a professor of International Law, represented Poland at the League of Nations in the interwar period, specialising in the complicated sovereignty of the disputed territory of Silesia, with its Polish, German and Czechoslovak claims. ¹

.

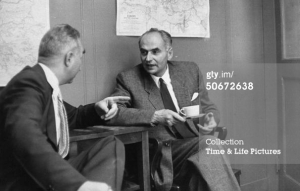

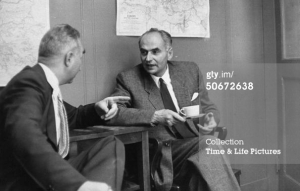

Marek after his defection from the Polish People’s Republic United Nations delegation in New York (September 1953)

.

When World War II broke out, Marek made his way east (visiting my father and grandparents briefly in Lwów), before escaping through Romania and making his way to France. There he joined the Polish 5th Rifle Regiment and fought with the French Army until its surrender. A fluent francophone from the days of his post-graduate studies in France and Switzerland, he joined the intellectual underground, producing books and pamphlets denigrating fascism and communism. As he would later describe in his book W Polsce pod Sowieckim Jarzmem (“In Poland Under the Red Yolk”), he made the fateful decision to return to Poland in 1946 to recommence his work as a professor.² He is best remembered for his dramatic escape from the Polish People’s Republic in 1953 by renouncing his diplomatic credentials to the United Nations in New York.

.

Cutting through the unopened pages with a paper-knife holds a specific fascination, not only for the light it shines on the personal circumstances of Marek in occupied France, but also for the aptness of its theme. That a man whose expertise is International Law should be going back to the drawing board in the midst of a brutal war in which every edifice and instrument of law seemed to have failed, and failed spectacularly, perhaps shows the tenacity of his choice of profession; but knowing as I do that he had lost his parents, siblings, and cousins in that war, had been living in exile and in fear of arrest, and within two years is going to return to his Polish homeland to discover that any hope of a just society there based on the rule of law will be crushed by a Soviet policy of political interference, administrative manipulation and the threat of military force makes the pages turn with a fatalism that stems from this reader’s qualified omniscience.

.

The final page notes that this book was written in Chambéry and Grenoble between March 1943 and March 1944. Marek was then working with the resistance movement. Following Italian occupation, the Germans invaded Grenoble in September 1943. The self-styled capital of the Maquis witnessed a year of sabotage, ambush, and brutal retaliation before the Germans finally withdrew on 22nd August 1944.

.

Marek survived the war in the French underground. As he was all too aware by the time he published this book in 1945, with the war finally at an end, the toll his own family had paid for being Jewish, or Polish, or educated would become tragically clear. His father had been successful Jewish lumber merchant Joachim Kornreich. Although Marek adopted the Polish surname Korowicz from the start of the Second Republic in 1918 and became a Catholic through marriage, his choice of profession and not his ethnic origins could very well have resulted in his extra-judicial murder if he had not managed to escape from occupied Poland in 1939. That was in fact the fate of his brother and fellow professor, my grandfather Henryk Korowicz who was murdered in Lwów in July 1941 along with 24 of his colleagues.

.

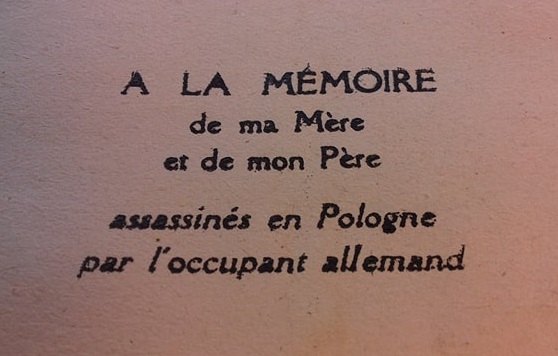

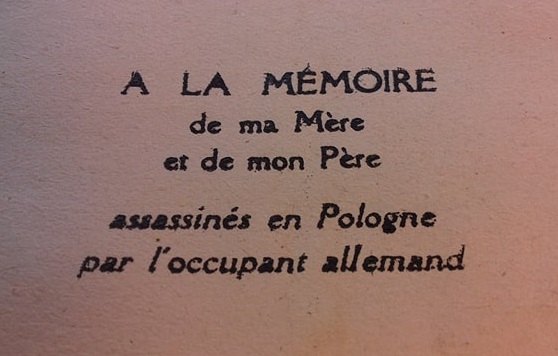

Marek dedicates the book to his parents whom he was not to see again. Eighty-year old Joachim was beaten to death by German soldiers in Lublin in 1939. Joachim’s wife Gisela disappeared into that charnel house of human slaughter where international law had been most ineffective.

.

“To the memory of my Mother and my Father, murdered in Poland by the German occupier.”

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Marek was Head of the Polish-German Geneva Convention Division at the Government of Silesia (1929-1937); Director Polish Minorities Office of Upper Silesia, representing Polish authorities before the Upper-Silesian Mixed Commission until the termination of the Geneva Convention (1932-1937); Polish Member of the Arbitral Commission for Border Crossing Permits in Upper Silesia (1933-1937); Commissioner General of Poland for the exchange of archives with Germany in Upper Silesia (1933-1937); assistant to the Polish Agent before the Permanent Court of International Justice (1931); legal expert of Poland to the League of Nations (1934,1935), and to the Polish-Czechoslovak Conference (January-March 1939) in Prague.

2. Marek’s academic career began at the Jagiellonian University in 1926; he was volunt. assistant to the chair of international and constitutional law (1928/29); lecturer in international law at the School of Social and Economic Sciences in Katowice (1936-1939); head of the Academic Division of the Polish YMCA in France and secr. gen. of the Polish Centre of Higher Studies in Paris (1944-1946); since April 1946, successively or simultaneously professor and dean (3 years) at the School Public Administration in Katowice teaching int. and const. law; associate professor (docent) of int. law Warsaw University (1947); prof. of int. law Lublin University; finally returned to his own Jagiellonian Univ. as prof of int. law until his arrival in Sept. 1953 in the USA; since Feb. 1954, research professor of int. law and organization at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, admin. by Tufts and Harvard Universities.

.

I have covered the circumstances of my granduncle Marek Korowicz’s escape from the Polish Delegation to the United Nations in 1953 in this previous post. Below Marek tells the story in his own words. He was called to give testimony before a specially-convened sub-committee of the Committee on Un-American Activities, a week after his arrival in New York to take up the position of President of the Sixth Committee (Legal) of the United Nations General Assembly. Of course, he never occupied that post, denouncing his credentials and condemning the Polish and Soviet governments.

.

19th September 1953 Dr. Marek Stanislaw Korowicz (R) talking to Stefan Korboński (the last chief of the Polish Underground) before the press conference announcing his appeal for political asylum in the US. (Photo by Peter Stackpole//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

.

The content and format of Marek’s testimony are very much a reflection of the heightened tensions, mutual mistrust, and fatalism which characterized the Cold War. This is only six months after Joesph Stalin’s death. The Soviet Union, enigmatic, despotic and a recent ally, is the subject of foreboding speculation on the part of the US government. Marek is quizzed on topical matters behind the Iron Curtain. What has happened to Beria, who seemed poised to replace Stalin but now has disappeared? What is the state of the USSR’s atomic programme? Do they have a hydrogen bomb? The questions and answers in a general sense would not be out of place in a Hollywood screenplay, a familiarity which in retrospect downplays the high stakes of the era. Marek had certainly placed himself in considerable danger. His protection was precisely the public fora in which he told his story, not just here at US Federal buildings, but in the press conferences and radio broadcasts he gave throughout this period. The fact that he was a professor of international law and had worked extensively as a diplomat before the second world war, lent his testimony greater impact. The details he employs to compare the standard of living and civil freedoms between East and West – the number of cars, television sets, the presence of Soviet military garrisons throughout the satellite states, the role of the Catholic Church, and the propaganda battle between state broadcasters and the Voice of America- are born out of the experiences of an inveterate opponent of foreign control (he was among other things a veteran of the 1920 Polish-Soviet War) and are conveyed with professorial exactness.

The benefit of hindsight may soften somewhat the atmosphere of impending doom which no doubt percolated the era, when it was considered not only conceivable but even logical to destroy the world in order to save it from itself. And yet there is still something haunting in the attribution of the Katyń massacres to Nazi Germany by the House Un-American Activities Committee Chairman Harold Velde in the following exchange:

.

Dr. KOROWICZ. It must be well understood that the Polish people keep in their minds today a vivid memory of all the Hitlerite atrocities committed by these Germans. Six million Poles were savagely butchered. But in spite of this the Polish people would like to live in peace and in definite peace with their neighbouring German populations.

Mr. VELDE. You are referring to the butchering of the Poles by the Hitlerites. I wonder if you are referring there to the Katyń Forest massacre?

Dr. KOROWICZ. With respect to Katyń, Mr. Chairman, the opinion in Poland is almost unanimous that the assassination and murder of so many Polish officers was a guilty deed performed by the Russians and not by the Germans.

.

Of course, the families of the 22,000 Polish prisoners, executed in 1940 on the orders of Stalin and the Politburo, would have to wait until 1990 when Gorbachev admitted the coverup. There was a grotesque Orwellian pantomime in the methods used by the Soviet Union to turn their own self-documented crime into that of the Germans, from the ludicrous “Special Commission for Determination and Investigation of the Shooting of Polish Prisoners of War by German-Fascist Invaders in Katyn Forest” via the Nuremberg Trials right down to today when many of the copious volumes of files about Katyń in the Russian archives still remain sealed. It would indeed be strange that Chairman Velde would categorize in error Katyń as a Nazi crime when only the previous year the Congressional Investigation known as the Madden Committee concluded that Soviets were indeed the culprits. It is for rhetorical effect, and moreover, to have the Polish defector make the accusation himself.

.

Anyway, over to Marek and the Committee members, and some old-fashioned Cold War drama:

.

Marek as star witness before Special House Committee on Communist Aggression

.

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 1953

.

UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE

ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES,

Washington, D.C.

.

PUBLIC HEARING

.

The subcommittee of the Committee on Un-American Activities met, pursuant to call, at 10.40 a.m. in the caucus room, 362 Old House Office Building, Hon. Harold H. Velde (chairman) presiding.

Committee members present: Representatives Harold H. Velde (chairman), Gordon H. Scherer, and James B. Frazier, Jr.

Staff members present: Robert L. Kunzig, counsel; Frank S. Tavenner, Jr., counsel; Louis J. Russell {trivia: who may later have been the sixth Watergate burglar}, chief investigator; Raphael I. Nixon, director of research; George E. Cooper, investigator.

Mr. VELDE. Will the witness please rise. Dr. Korowicz, in the testimony you are about to give before this subcommittee of the House of Representatives, do you solemnly swear that you will tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth so help you God?

Dr. KOROWICZ. Yes. I do.

Mr. VELDE. Proceed, Mr. Counsel.

Mr. KUNZIG. Dr. Korowicz, would you describe to the committee what event transpired on September 1 of this year, just a few weeks ago?

Read the rest of this entry »

Uncle Marek (Photographer: Alfred Eisenstaedt- LIFE)

“Just before dawn one day last week, a greying, carefully dressed man left his twelfth-floor room in Manhattan’s Chatham Hotel, where he was staying with the other members of Communist Poland’s U.N. delegation. Suitcase in hand, he tiptoed down the fire stairs to the ninth floor, then took the elevator to the lobby. He left the hotel, went to the phone booth in an all-night restaurant nearby and dialed a Manhattan number. After a short conversation in Polish, he left the restaurant and hailed a taxi. In this manner, Dr. Marek Korowicz, 50, professor of international law at Cracow University and the top legal adviser to the delegation, made his way out from behind the Iron Curtain.”

TIME, September 22nd, 1953

.

My father who escaped from Lwów in summer 1945 was living in Ireland three years later. From time to time, he still received a surprise from the world beyond the Iron Curtain. His father’s brother Marek was supposed to be stuck lecturing in Kraków (while privately cursing the Polish authorities). And now the newspapers were suddenly full of his photo next to the revelation: POLISH UN DIPLOMAT SEEKS POLITICAL ASYLUM IN US. It seemed incongruous to Wojtek that Uncle Marek, a congenial academic who had worked as a law professor and diplomat before the war, was suddenly the epitome of Cold War daring. Not that Marek was lacking in the political and military credentials befitting an anti-Communist hero (so much craved in the West); it was simply the fact that Marek was, well, ‘Uncle Marek.’

Marek, who made his reputation in the field of sovereignty in international law, worked in the Upper Silesian Voivodship between 1929-39.[1] When the war broke out, he first fled east (visiting my father and grandparents briefly in Lwów), before escaping through Romania and making his way to France. There he joined the Polish 5th Rifle Regiment and fought with the French Army until its surrender. He later joined the intellectual underground, producing books and pamphlets denigrating the rise of fascism and communism alike. In 1946, he returned to Poland as a much-needed professor, accepting the Soviet-backed government’s assurances that the educational system would be untouched by political interference. It didn’t take him long to realize he was trapped. He worked as professor and dean at the Law Dept. in Katowice University, and was an associate professor at the Warsaw and Lublin Universities, before moving back to his alma mater, the Jagiellonien University in Kraków. He knew he would never leave if he actively opposed the Communist regime and saw, like many Polish academics, the value of saving the minds of young Poland, by working within the system. He avoided all contact with Party activities, taught a prescribed syllabus, put up with the classroom spies who reported on his lectures, and then gathered the best of his pupils after hours and lectured the unexpurgated version of international law.

Marek is best remembered for his escape from Poland in 1953. His achievement was as much in the manner of his escape as in the result itself. He can rightly claim to have single-handedly wiped the smiles off the faces of the Soviet and Polish Delegations at the United Nations General Assembly; and there are photos to prove it. He could not have found a more public forum to expose many of the fantasies the Soviets proselytised in the West about the earthly paradise they claimed was Communism.

.

Marek announcing his defection before the world’s media. Photographer:Peter Stackpole LIFE

.

Marek was handed his moment of destiny when Poland was awarded the rotating chairmanship of the UN Legal Committee of the General Assembly in 1953. Polish Head of Delegation Juliusz Katz-Suchy, was forced to bolster the weak legal skills of his Communist diplomatic cadre with a genuine specialist. And when Marek was summoned, he thought they had made a mistake; they never allowed non-Party members out unless they had at least a family member to hold hostage in the country. He was divorced and had no children. Only on the eve of the delegation’s departure did Foreign Minister Skrzeszewski discover the oversight, but it was already too late and they obviously decided to take the risk. The delegation traveled to France to take the transatlantic crossing on the aptly named Liberté. Until the last moment, Marek had to endure the innate distrust and suspicions of delegate colleagues. His suitcase was searched, his movements watched. All the delegates were told when they reached America not to engage the capitalists in conversation and Marek was scolded by Katz-Suchy for talking to the elevator attendant at the Chatham Hotel, in New York. It was from there that he made his escape. He walked out in the fresh Manhattan morning air, and enjoyed the exhilaration of freedom, which he had not felt since before his return to Poland in 1946. He phoned Stefan Korboński (who himself had fled Poland five years previously), and within a short time Uncle Marek was the breaking news amidst headlines which spread throughout the Western World. POLISH DIPLOMAT FLEES RED TERROR. REVEALS HORROR OF COMMUNIST SYSTEM. THE BIGGEST FISH WE HAVE EVER CAUGHT. He informed UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold and President of the General Assembly Madame Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit of his decision to renounce his credentials, saying that it was ‘absolutely impossible for me to collaborate with these representatives—not of my beloved country—but solely of the Soviet regime in Poland.’ Marek was put under 24-hour FBI protection. Assassination was a real threat and The Chicago Tribune claimed that ‘at least 18 known agents of Russia or Red satellite nations carry guns’ on the streets of New York while claiming diplomatic immunity.[2] It was the height of McCarthyism; within a week of his arrival in the US, he was testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was detailed and blunt, warning of Communist expansionism, through political and industrial espionage. He urged the breaking off of all diplomatic and trade relations with the Soviet Union as the best method of checking the spread of Communism.

.

Marek (Left) speaking on Radio Free Europe with Stefan Korboński (Right) Photo

.

Those newspaper headlines and interviews from New York to Hobart, reveal the polarization of a political and social feud which would frame the lives and deaths of the following two generations: IF I WERE A DIPLOMAT FOR THE WEST…, POLE ALLEGES RUSSIAN WORLD PLOT. REDS HOPE FOR WORLD CONQUEST BY 1970 OR 1980, POLE TELLS: WHY I QUIT THE REDS. Marek’s defection was emblematic of an intrigue becoming of the danger and suspense which were fast becoming the hallmarks of Cold War politics, when America’s wartime ally became its peacetime foe. Since the end of the Second World War, the Soviet Union and United States firmly staked out the citadels of their prospective empires on the map of the world. Starting in Europe, and as agreed at Yalta and Potsdam, the line went from the Baltic Sea, through defeated Germany down to the Dalmatian Coast. Stalin’s ruthlessness in violently suppressing any notion of independent rule in Eastern Europe by producing his own local Communist governments backed by Soviet tanks, was as foreboding to the Americans as it was disastrous to the peoples of Czechoslovakia, Romania, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Albania. If the trial of the leaders of the Polish Underground on charges of terrorism in 1945 and the Czechoslovak coup d’état of 1948 demonstrated the unrefined but effective tactics of Soviet expansionism, then the American and British reaction to the Berlin Blockade showed to what extent the Western Allies were willing to go in order to check the Soviet advance. When Truman and Atlee could no longer deny that abandoning the little Europeans of the East to the whims of Stalin would never be enough to ensure a secure and cooperative Soviet Union, then perhaps there was a brief moment of opportunity for bolstering the independence movements of the smaller nations. But that final window, a chance to prevent fifty years of proxy wars, only lasted from May 12th1949, when the red-faced Soviets lifted the blockade from Berlin, until August 29th when a 22 megaton Atomic bomb was exploded in a testing ground in Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan. With the Soviets now content members of the atomic club, the Cold War would change gear and move further afield to test its participants’ will for a fight.

.

Head of Polish Delegation Juliusz Katz-Suchy breaks the news of Marek’s defection to USSR Delegation Chief Malik (LIFE)

.

In exile, Marek was granted asylum and offered the post of Professor of International Law at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. He continued to publish books on legal issues and an autobiographical account of life in Communist Poland. He died in 1964 still missing his favourite Tatras. He was a keen mountaineer and had been a founding member of the Katowice Mountaineering Club. The villain of the story, Head of Delegation Juliusz Katz-Suchy, who played unflattering foil to Marek’s knight of anti-communism, was himself not immune to the vagueries of politics. As a UN representative, his colourful invective had already made him a favourite of journalists ‘who noted he even spiced his Marxist denunciations of the U.S. as warmonger, slavemaster and cannibal with quotations from Shakespeare.’[3] In a LIFE magazine article on Marek’s defection, the caption beneath Katz-Suchy’s image reads: “Boss of delegation was a vain braggard, Juliusz Katz-Suchy. The author [Marek] was impressed by the fact his ignorance was matched only by his ill breeding. On his way over, French food did not satisfy him.” Katz-Suchy’s communist credentials which had once conferred upon him the privileges of power would not protect him from the anti-Zionist campaign in Poland, which followed 1967’s Six Day War. He felt forced to emigrate to Denmark in 1969, and died, like Marek, in exile.

As for Marek, the pleasure of living in a country where he could express his opinions openly was tainted by his separation from the land he loved and wished to be. When he described his defection and posed himself the question the journalists had asked, whether he had done so out of some sense of patriotic heroism or self preservation, he answered:

“It was neither. I had to do it simply because I couldn’t sit down with people who in Poland are considered Soviet agents, oppressors of the nation, and some, even murderers. I had to do it because if I sat down with these people in the “Polish” foreign delegation, after returning home, my best friends, old buddies from different walks of life and of a common struggle, would avoid me, and perhaps not even shake hands with me. For honest Poles, I would have become a regime man and that carries the most terrible stigma. That’s why I had to leave everything I had, leave behind the dearest people, and abandon my students.”

—————————————————————————————————————-

[1] The Polish-administered part of the territory of Silesia, disputed by Poles, Germans, and Czechs. Following uprisings of Poles in German-occupied Silesia in 1919-21, the German-Polish Accord on East Silesia saw shared sovereignty and relative peace until 1939.

[2] Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1953, sec.1. p.2.